http://public.web.cern.ch/Public/Welcome.html

|

||

|---|---|---|

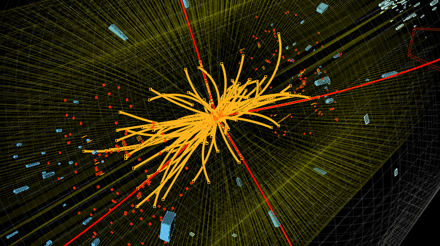

| Proton-proton collision in the CMS experiment producing four high-energy muons (red lines). The event shows characteristics expected from the decay of a Higgs boson but it is also consistent with background Standard Model physics processes (Image: CMS) | ||

At a seminar on 4 July, the ATLAS and CMS experiments at CERN presented their latest results in the search for the long-sought Higgs boson. Both experiments see strong indications for the presence of a new particle, which could be the Higgs boson, in the mass region around 126 gigaelectronvolts (GeV). Both ATLAS and CMS gave the level of significance of the result as 5 sigma on the scale that particle physicists use to describe the certainty of a discovery. One sigma means the results could be random fluctuations in the data, 3 sigma counts as an observation and a 5-sigma result is a discovery. The results presented today are preliminary, as the data from 2012 is still under analysis. The complete analysis is expected to be published around the end of July. The Standard Model successfully describes all of the elementary particles we know to exist and how they interact with one another. But our understanding of nature is incomplete. In particular, the Standard Model cannot answer one basic question: Why do most of these elementary particles have masses? Without mass, the universe would be a very different place. For example, if the electron had no mass, there would be no atoms. Hence there would be no ordinary matter as we know it, no chemistry, no biology and no people. In addition, the Sun shines thanks to a delicate interplay among the fundamental forces of nature, which would be completely upset if some of those force particles did not have large masses. At first sight the concept of mass seems not to fit into the Standard Model of particle physics. Two of the forces the model describes – electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force – can be described by a single theory, that of the electroweak force. Scientists have subjected the electroweak theory to many experimental tests, which it has passed with flying colours. However, the basic equations of the theory seem to require all elementary particles to be massless. Scientists needed a way out of this conundrum. Several physicists, including Peter Higgs, discovered a mechanism that, if added to the equations, would allow particles to have masses. This is now known as the Higgs mechanism. Integrating it into the Standard Model allowed scientists to make predictions of various quantities, including the mass of the heaviest known particle, the top quark. Experimentalists found this particle just where equations using the Higgs mechanism predicted it should be. According to theory, the Higgs mechanism works as a medium that exists everywhere in space. Particles gain mass by interacting with this medium. Peter Higgs pointed out that the mechanism required the existence of an unseen particle, which we now call the Higgs boson. The Higgs boson is the fundamental component of the Higgs medium, much as the photon is the fundamental component of light. The Higgs boson is the only particle predicted by the Standard Model that has not yet been seen by experiments. The Higgs mechanism does not predict the mass of the Higgs boson itself but rather a range of masses. Fortunately, the Higgs boson would leave a unique particle footprint depending on its mass. So scientists know what to look for and would be able to calculate its mass from the particles they saw in the detector. Experimentalists might find that the Higgs boson is different from the simplest version the Standard Model predicts. Many theories that describe physics beyond the Standard Model, such as supersymmetry and composite models, suggest the existence of a zoo of new particles, including different kinds of Higgs bosons. If any of these scenarios turn out to be true, finding the Higgs boson could be a gateway to discovering new physics, such as superparticles or dark matter. On the other hand, finding no Higgs boson at the LHC would give credence to another class of theories that explain the Higgs mechanism in different ways.

|

||

|